FSIN calls for charges against farmers involved in land dispute

The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) is demanding that the RCMP charge a family of farmers after they were found on land from which they had been evicted by the Ochapowace First Nation east of Regina.

The Ochapowace band and the Cunday family have been at odds since late March over a parcel of land the Cundays leased from the band for the purpose of farming.

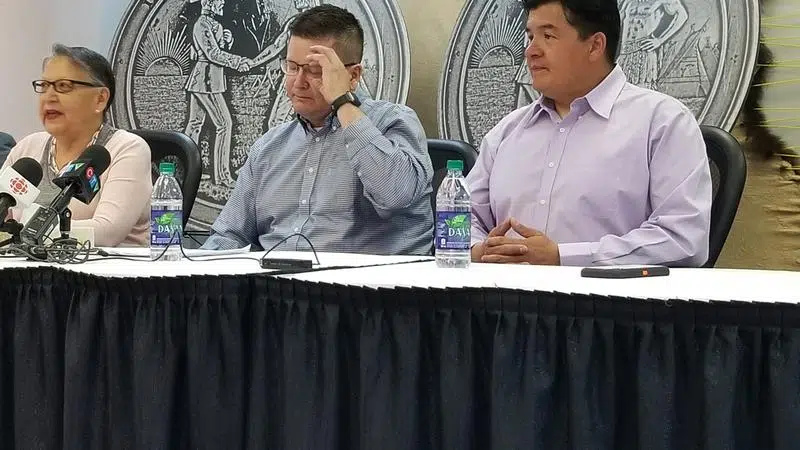

At a media conference Thursday in Saskatoon, Ochapowace Chief Margaret Bear and Ochapowace lands manager Tim Bear laid out their timeline of events concerning the dispute.