Meet the Elders of the Athabasca Denesuline Education Authority

Indigenous elders provide cultural and spiritual guidance. They often lead ceremonies with prayer and make themselves available for individual and group consultations but being an elder is more than just a designation – it’s an opportunity to share wisdom and insight to help shape a new generation of Indigenous people.

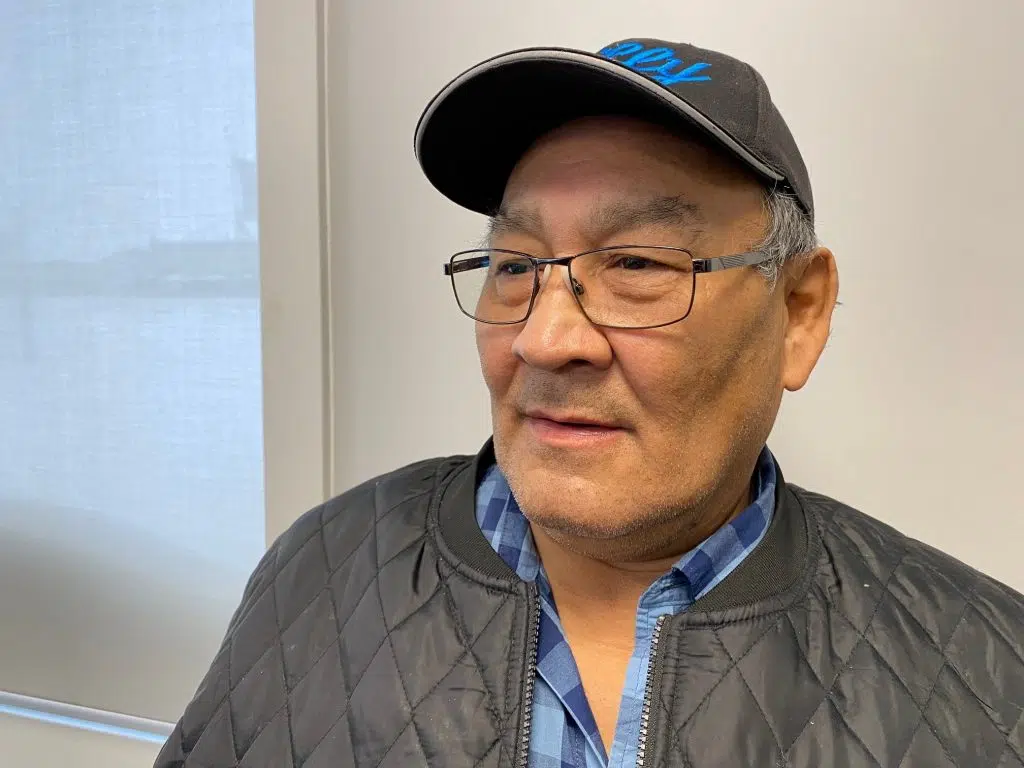

Elder Billy Joe Mercredi